Last November I was fortunate enough to have dinner in one of Beirut’s best restaurants, Em Sherif, with a group of Lebanese winemakers. There was no menu, they just bring you seemingly endless small dishes such as Kibbeh nayyeh, finely chopped raw lamb with onions, or baby aubergines stuffed with walnuts. Each one was more delicious than the last though I made the schoolboy error of filling up on the insanely good hummus and flatbread at the beginning. Mezze really isn’t designed for greedy Englishmen. Along with the food we had some excellent local wines but one of the winemakers admitted to me that the best thing with mezze isn’t wine, it’s Arak. This aniseed spirit drunk diluted with water and ice, cleans the palate and sharpens the appetite so you’re ready for a bite of something different. I looked around the restaurant and most of the fantastically glamorous clientele (everyone in Beirut is very chic) were all drinking Arak.

Arak is part of a family of aniseed-flavoured spirits that exist all over the Mediterranean and Middle East. The word comes from the Arabic for sweat: a description of the alcohol dripping off the still. There’s Raki in Turkey, Rakia in Bulgaria and Ouzo in Greece. Further afield there’s Sambuca in Italy, Anis in Spain and Pastis in France. In fact about the only country in Europe that doesn’t do something similar is Britain.

Though Arak is similar to its Greek and Turkish cousins, it’s a generally a far superior product. Michael Karam author of a Arak and Mezze: the taste of Lebanon told me “the Lebanese are very quality driven. There is no industrial Lebanese Arak.” It’s only ever made from a spirit distilled from locally-grown grapes rather than the neutral alcohol more common in Europe. I visited Domaine des Tourelles in the Bekaa valley who make Arak Brun which according to Michael Karam is “considered by the Lebanese to be the gold standard”. It was November and they were still bringing in grapes for Arak production mainly Obaideh and Merwah but also some Cinsault. The grapes are gently pressed and the juice run off for fermentation in enormous concrete tanks. No sulphur can be added or it would be accentuated during distillation and they use wild yeasts for fermentation.

Faouzi Issa from Tourelles with his arak-craving face

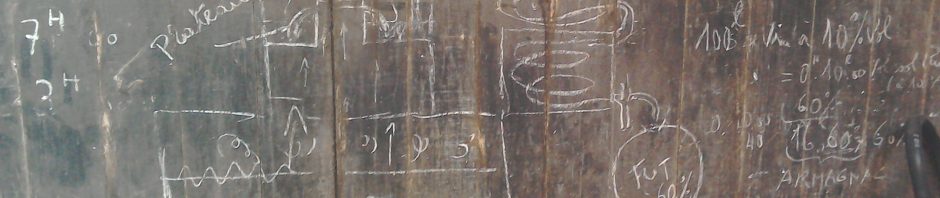

The winery is a living museum. They use a 19th century copper alembic that was made in Aleppo in Syria for distillation. The aniseed comes from Syria too, a village called Hina.. There are sacks of it piled high everywhere like sandbags, insurance in case the war cuts off supply. Damascus is only 40 miles away. The wine is distilled twice to create an eau-de-vie and then once more with aniseed. “We make arak 330 days a year, making it in small batches like this is very costly” according to Faouzi Issa from the family who own Tourelles.

They then age Arak Brun for one year and the Special Reserve for five in clay jars similar to classical amphora but with flat bottoms. Recently they wanted to expand production but nobody knew how to make the jars. Luckily they found a 70 year old man in a remote village who was probably the last person with the requisite knowledge. They have now started a workshop making jars where younger men can learn the necessary skills. It’s a slow labour intensive process so they can only make 30 to 40 jars per year.

Arak ageing at Tourelles

At Clos St Thomas just up the road from Tourelles, they make Arak Touma. Here I tried the pre-aniseed eau-de-vie which tastes a little like an unaged Armagnac crossed with rum. The flavour of this high quality spirit doesn’t need disguising with sugar which explains why good Arak is so refreshing. Said Touma, the patriarch of the family, showed me how to add water from a height into the arak so that it goes cloudy, “louching” is the technical term. You generally drink it in a ratio of two parts water to one Arak with ice. I was gently reprimanded by Michael Karam for adding too much water – “your Arak looks a little weak” he told me.

The ageing and care at every stage of production makes Lebanese Arak so much smoother than Ouzo or Raki. In fact for a drink so strong, usually around 50%, it’s dangerously drinkable. Once you’ve acquired a taste for it you’ll be like Faouzi Issa who said that when he is away from Lebanon: “I crave Arak” . Michael Karam told me “as one drinks sake with sushi, I dream of the day when people will eat Lebanese food and drink arak.” With the growth of Middle Eastern food across America and Europe, Michael’s dream might just come true.

A version of this article appeared in Food & Wine magazine.

Pingback: I wish I lived nearer O Gourmet Libanais | Henry's World of Booze

Arak Brun is my favorite Lebanese Arak. Arak Al Mimas is my favorite Syrian Brand. Jordan – sorry, all their stuff is gross, and for Palestine, Arak Muaddi is the best. I think it might even be my favorite overall. They’re not that known, but boy are they good. You can check them out at: http://www.muaddi.com